Do Extreme Records Favor Earlier Events?

SEARCH BLOG: CLIMATE

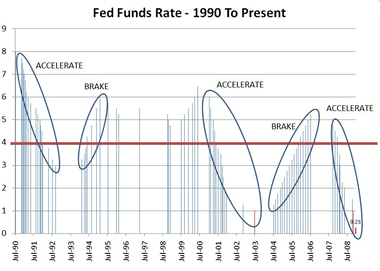

Over the past few weeks, I have published various perspectives related to my macro-analysis of the U.S. Climate based on statewide, monthly extreme temperature records. Rather than use calculated averages and algorithmically adjusted data, this analysis depends on actual records over nearly 13 decades. The analysis challenged the thesis that there is a widespread global warming as evidenced by the increased frequency of new record temperature extremes.

- the 1930s were, by far, the warmest recorded decade

- the 1990s were no more "extreme" than an average decade

- the 2000s have been far less "extreme" than most decades

Bruce, I forgot to mention - the hallofrecord study doesn't pass my gut check. Any measure of records of a given items is always going to favor earlier events.

In a very short time series, let's say a few years, there will be insufficient opportunity to determine if the data represent low, normal, or high values related to a longer time series. The "all-time" monthly records require 600 values. This is 50 states times 12 months.

- These are maximums of all recording stations from 50 states times 365 days of observation: 18,250 statewide daily maximums consolidated to the 12 monthly extremes for the 50 states.

- In one decade, the 600 records are based on 182,500 maximums [I'm ignoring leap years.]

- In the 129 years of the timeline used in my study, there were 2,354,250 daily statewide maximums used to establish the 600 records... a reasonable "sampling."

Because these records are based on absolute temperatures and tie-goes-to-the-latest methodology, there is no favoring earlier points after a reasonable time has passed... and 129 years and 2,354,250 daily observations is more than reasonable.

In fact, the methodology actually biases toward the latest occurrences... because it is a replacement methodology, not an additive one.

Stated another way, if the number of records that occurred in a year were kept forever as the basis a growing count, then the bias would be toward the earlier years which had the easiest opportunity to set records. But, because the number of records for a year is reduced when tied or surpassed by a later year as the basis of a constant count, there can be no long-term bias toward early years.

If the proposition that earlier years were favored were true, then one would expect that the highest incident would have been the beginning decade of the 1880s... which happen to have the lowest incident with only 3 maximum records.What doesn't pass the test is... the "gut check" which was another way of saying that "I didn't really examine the numbers." I hope "misterjosh" now understands the reason why this is a valid analysis.

..