A Critique of the October 2009 NCAR Study Regarding Record Maximum to Minimum Ratios

SEARCH BLOG: GLOBAL WARMING

This is a critique of the October 2009 NCAR publication regarding increasing ratio of new daily maximum temperatures to new daily minimum temperatures.

The NCAR [National Center for Atmospheric Research] study titled “The relative increase of record high maximum temperatures compared to record low minimum temperatures in the U.S.” was published October 19, 2009.

"AbstractThe following is a graphic representation of the study from the UCAR website:

The current observed value of the ratio of daily record high maximum temperatures to record low minimum temperatures averaged across the U.S. is about two to one. This is because records that were declining uniformly earlier in the 20th century following a decay proportional to 1/n (n being the number of years since the beginning of record keeping) have been declining less slowly for record highs than record lows since the late 1970s. Model simulations of U.S. 20th century climate show a greater ratio of about four to one due to more uniform warming across the U.S. than in observations. Following an A1B emission scenario for the 21st century, the U.S. ratio of record high maximum to record low minimum temperatures is projected to continue to increase, with ratios of about 20 to 1 by mid-century, and roughly 50 to 1 by the end of the century."

While this study does use sound methodology regarding the data it has included, it falls short of being both statistically and scientifically complete. Hence, the conclusions from this study are prone to significant bias and any projections from this study are likely incorrect."This graphic shows the ratio of record daily highs to record daily lows observed at about 1,800 weather stations in the 48 contiguous United States from January 1950 through September 2009. Each bar shows the proportion of record highs (red) to record lows (blue)for each decade. The 1960s and 1970s saw slightly more record daily lows than highs, but in the last 30 years record highs have increasingly predominated, with the ratio now about two-to-one for the 48 states as a whole."

Study's Methodology

"We use a subset of quality controlled NCDC US COOP network station observations of daily maximum and minimum temperatures, retaining only those stations with less than 10% missing data (in fact the median number of missing records over all stations is 2.6%, the mean number is 1.2%) . All stations record span the same period, from 1950 to 2006, to avoid any effect that would be introduced by a mix of shorter and longer records. The missing data are filled in by simple averages from neighboring days with reported values when there are no more than two consecutive days missing, or otherwise by interpolating values at the closest surrounding stations. Thus we do not expect extreme values to be introduced by this essentially smoothing procedure. In addition our results are always presented as totals over the entire continental U.S. region or its East and West portions, with hundreds of stations summed up. It is likely that record low minima for some stations are somewhat skewed to a cool bias (e.g. more record lows than should have occurred) due to changes of observing time (see discussion in Easterling, 2002, and discussion in auxiliary material), though this effect is considered to be minor and should not qualitatively change the results. Additionally, at some stations two types of thermometers were used to record maximum and minimum temperatures. The switch to the Max/Min Temperature System (MMTS) in the 1980s at about half the stations means that thermistor measurements are made for maximum and minimum. This has been documented by Quayle et al. (1991), and the effect is also considered to be small. To address this issue, an analysis of records within temperature minima and within temperature maxima shows that the record minimum temperatures are providing most of the signal of the increasing ratio of record highs to record lows (see further discussion in auxiliary material)." [lines 82-102 NCAR publication]Comments

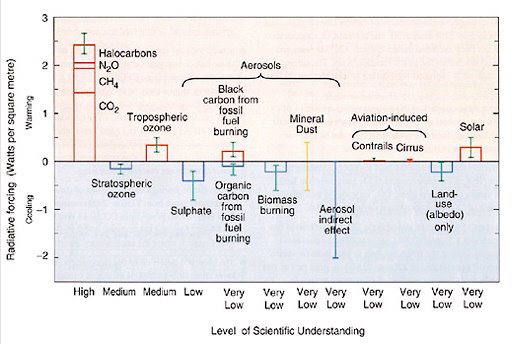

The NCAR Study contains at least two biases:

- The selection of 1950 through 2006 significantly biases the outcome of this study because the U.S. was entering a cooling period in the 1960s and 1970s which creates the illusion of unusual subsequent warming from 1980 through 2006.

- During the last decade, a large reduction of rural reporting stations in the U.S. has biased records toward urbanized and urbanizing areas. Land use changes as well as deterioration of urban siting versus NOAA standards [http://www.surfacestations.org/] have resulted in a bias toward over-reporting/erroneous reporting of high temperature records and an under-reporting of low temperature records.

Reference for site ratings: NOAA's Climate Reference Network Site Handbook Section 2.2.1

As stated earlier, this critique does not question the statistical methodology applied for that data used in the study. Rather it challenges the underlying selection of the data and the quality of the data.

The most obvious deficiency to anyone familiar with tracking U.S. temperature records is the omission of data from the 1880s through the 1940s. By selecting a period of cooling as the starting point, the NCAR study “stacks the deck” in favor of a warming trend. This is the same problem with the 1880s as a starting point for the longer term trend, but due to shorter cyclical variations within the 130 years longer trend data are somewhat tempered. There is no full climate cycle in the NCAR study.

To demonstrate this point, we will compare the record of statewide monthly temperature records for the longer period with the approximately 60-years of data used in the NCAR study. Obviously, comparing monthly statewide records to daily single point records can be argued a case of apple seeds and watermelons, but from an analytical perspective it is reasonable, as shall be shown.

The real difference is that we are comparing area climates with micro climates. Area climate monthly data maximum and minimum records will rarely be affected by spurious readings whereas micro climate daily data is wholly dependent upon very specific proper siting and quality control, including avoidance of external heat sources, issues that have been raised at the Surface Stations website.

In February 2007, I published an analysis titled, “Extreme Temperatures – Where’s The Global Warming” and a subsequent data update in January 2009 titled “Where Is The Global Warming... Extreme Temperature Records Update January 2009.” Dr. Roger Pielke, Sr. provided suggestions and a review in his weblog, “Climate Science.” In February 2009, these data were summarized graphically with this animation and data table in a posted titled, “Decadal Occurrences Of Statewide Maximum Temperature Records”:

Each state can have only 12 statewide, monthly records for the 13 decades tracked here... hence, they are "all-time" records for a state for a month.

Range goes from 0 [white] to 8 [dark red]. Indiana had the highest frequency of records in one decade with 8 still standing from the 1930s. See the table below for the actual count by decade. Old records are replaced if tied or surpassed by subsequent readings.

The 1930s experienced the highest number of maximum extreme temperatures for which records have not been tied or surpassed subsequently. While the late 1990s did have a very brief hot period associated with El Nino, the 1990s were a rather ordinary period for extreme temperatures in the contiguous 48 states.I have excluded Alaska and Hawaii from this animation because they are distinct and separate climate zones. For the record, however, Alaska's decade of most frequent high temperature records was the 1970s with 4. Hawaii's decade of most records was the 1910s. Those data are included in the table below.The 1990s were only particularly hot, as reflected in these records, in New England and Idaho. These selective areas were far more restricted than the geographically widespread heat of the 1930s.

This animation goes to the heart of my arguments regarding global warming as it is reflected in U.S. temperature data.

- The trendline used by those claiming a long term warming begins in a very cool climate period. Consequently, any trend from that point will be upward.

- The late 1990s were an aberration and not indicative of the general climate oscillations presented in these records.

Click on image below for larger view.

Each state can have only 12 maximum or minimum all-time monthly records. The methodology requires that any instance where a previous record is tied or exceeded, the old record in replaced by the newer record. Therefore, this approach has a slight bias toward more recent records due to the “tie goes to the later” rule.

Comparison of Statewide Monthly Temperature Records with the NCAR Study

Going back to the NCAR graphic we can see a trend which may correspond to their conclusion:

For later in the 21st century, the model indicates that as warming continues (following the A1B scenario), the ratio of record highs to record lows will continue to increase, with values of about 20 to 1 by mid-century, and roughly 50 to 1 by late century.

Two factors contribute to this increase as noted by Portman et al (2009a): 1) increases in temperature variance in a future warmer climate (as noted in the model by Meehl and Tebaldi, 2004), and 2) a future increasing trend of temperatures over the U.S. (model projections shown in Meehl et al., 2006). Since the A1B mid-range scenario is used, a lower forcing scenario (e.g. B1) produces reduced values of the ratio in the 21st century, and a higher forcing scenario (e.g. A2) produces greater values. The model cannot represent all aspects of unforced variability that may have influenced the observed changes of record temperatures to date, and the model over-estimates warming over the U.S. in the 20th century. The future projections may also reflect this tendency and somewhat over-estimate the future increase in the ratio. Under any future scenario that involves increases of anthropogenic greenhouse gases and corresponding increases in temperature, the ratio of record high maximum to record low minimum temperatures will continue to increase above the current value.

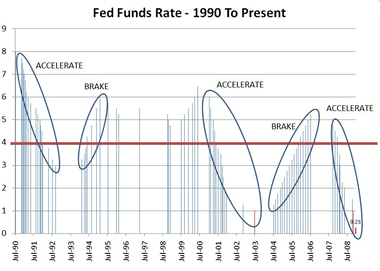

Before the direct comparison to the statewide monthly records, let us look at their extrapolation [FROM THE NCAR STUDY - "is projected to continue to increase, with ratios of about 20 to 1 by mid-century, and roughly 50 to 1 by the end of the century."] [my graphic]:

Before we can judge the extrapolation of maximum to minimum ratios in this study, we should understand how the data used by NCAR fits into the “big picture.”

Let us look at the statewide monthly maximum and minimum records by decade beginning in 1880. Those records are used to calculate a ratio of maximum and minimum records by decade and then compared with the NCAR study ratios.

There are two aspects of this comparison that jump out to the reader:

- The 1930s were, by far, the hottest period for the time frame. The ratio of maximum to minimum temperatures is greater in the 2000s, but the absolute number of monthly statewide extreme records is far less significant making the ratio far less significant.

- The general pattern of ratios for the monthly records follows reasonably closely to the pattern of the daily individual location records, on a decadal basis.

If you were to only look at the ratios of maximum to minimum monthly temperature records, it would be understandable to draw the conclusion that, while there was a cyclical pattern to the ratios, the ratios were increasing exponentially toward a much hotter environment.

If you were to only look at the ratios of maximum to minimum monthly temperature records, it would be understandable to draw the conclusion that, while there was a cyclical pattern to the ratios, the ratios were increasing exponentially toward a much hotter environment.It is only when you compare the absolute number of all-time records that you appreciate that ratios as a measure of global warming may be quite deficient. You should also note a significant divergence in the numerical trend of record high monthly versus daily records.

Keep in mind that there are significant biases toward recording daily warmer temperatures due to the closure of thousands of rural stations and expansion of urban areas into previously rural or suburban areas, creating enormous "heat sinks," that prevent night time temperatures from dropping to the extent that they would in a nearby rural setting. Hence more stations reporting greater frequencies of maximum temperatures and fewer minimums.

Keep in mind that there are significant biases toward recording daily warmer temperatures due to the closure of thousands of rural stations and expansion of urban areas into previously rural or suburban areas, creating enormous "heat sinks," that prevent night time temperatures from dropping to the extent that they would in a nearby rural setting. Hence more stations reporting greater frequencies of maximum temperatures and fewer minimums.Conclusion

The oscillating or cyclical nature of our climate is completely overlooked when one takes a small time frame such as the 1950s through 2006 and extrapolates a full century beyond. Even 130 years of data, starting from a relatively cold period, gives a very brief look at climate history for the U.S. and certainly one that is not sufficient to extrapolate a general warming trend, much less an accelerating one.

In the face of the recent decline in new all-time monthly statewide maximum records, it is more probable that we may be facing a cyclical decline in our overall temperature and that something similar to the 1960s and 1970s may be a far more realistic projection. Our most recent winters have been particularly colder than long-term averages and minimal sunspot activity may be another harbinger of this normal cyclical variation in our relatively stable climate.

For more information about this and related topics, please check out the following blogs:

The authors have contributed ideas and advice for this post.

..